by Alexandria Searls

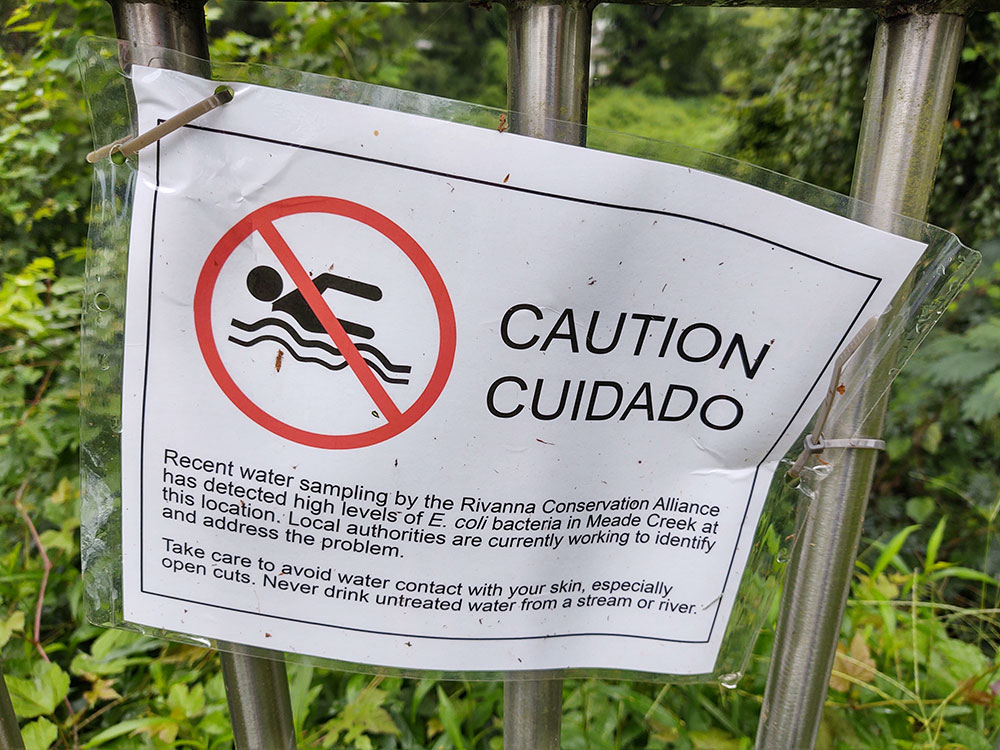

In November 2022, I reported on the high levels of E. coIi in Meade Creek, the stream that flows next to my house. Meade Creek at Meade Park had tested over 3000 MPN (the number of coliform organisms) on a scale that judged 410 MPN to be the outer limit of acceptable.

A water testing volunteer had given me some good news in early May, that the levels had gone down. Then one morning in late May I heard a knock at my door. Dressed in a Charlottesville Department of Utilities safety vest, in neon yellow and orange, a man was holding a cup of neon orange tablets. The news was not as glowing as the colors. The levels E. coli levels were back up, and they were trying to find the source of contamination. If there was a leak in the sewage pipes into the stream, the food dye would reveal it.

He placed some tablets in the lid of his cup and handed them to me. I went and put them in my bathtub, running the water so that the dye would head down the drain. The bathtub filled and the water turned bright yellow.

I returned the cap.

Later that day, returning from work, there was a Utilities truck next to our culvert. A worker was standing in the stream, holding a wire. In the truck there was a monitor showing the inside of the culvert. A remote camera on thick wheels was making its way through the culvert, searching for the bright yellow dye. So far, no dye, no leaks from the household sewage systems.

The men seemed to want to be anonymous, but they allowed me to take pictures and they answered my questions. There had been a good response from the neighborhood, and many households had flushed the tablets down their toilets and bathtubs. One utilities employee was seated in the back of the truck, maneuvering the camera. Another man, the one who had given me the tablets, was close to the monitor, communicating to the man in the stream. The monitor showed a fourth man at the other end of the culvert, closer to Meade Park.

As an underwater filmmaker, I was fascinated by the remote camera, which resembled a miniature moon buggy. It was moving slowly and climbing and descending rocks. It pivoted to examine the sides of the culvert. The tones were black and white and the stream of water milky.

“You’re going to be able to see the yellow dye?” I asked, uncertain.

“Yes,” I was told.

The camera made it out of the culvert and then plunged into Meade Creek, its lens completely underwater.

The underwater view was very familiar. The video footage resembled my own, rocks covered in short, fuzzy vegetation, bubbles and currents making their way through a murky waterscape.

I had filmed the stream at Meade Creek, before I knew the extent of the contamination.

Now I await the results of the exploration, and in the meantime, I’ll be looking for yellow dye. I’m not sure how long water can retain the dye, before it’s dispersed, but I’ll be looking for it anyway.